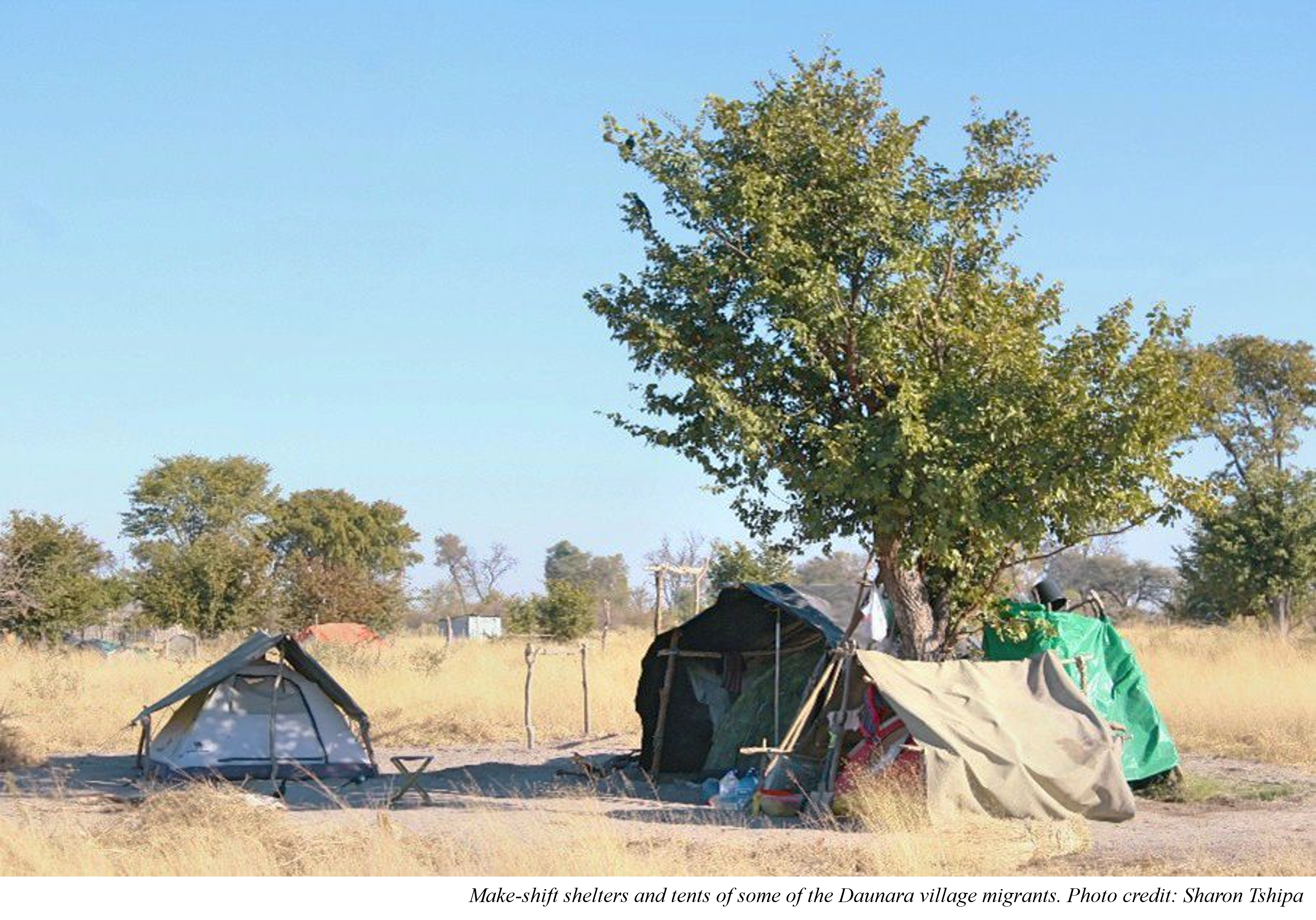

They are still there, camping in Daunara village while their homes wait with bated breath for the end of droughts and the arrival of flood waters to summon them home.

When the climate migrants arrived in Daunara village seven years ago, they thought their stay would be momentary, a season at the most. Little did they know that their wait would be as long as a river with no year of jubilee in sight, as climate scientists suggest that climate change is likely to increase evapotranspiration over the Okavango Delta.

What makes matters worse is that the Delta already loses 98% of its water to evapotranspiration. Further complicating the issue is the fact that water in the Delta comes almost completely from Angola—an average of 2.5 trillion gallons of water a year flow across the Caprivi Strip, a narrow band of Namibia, into Botswana— but droughts and development projects in Angola and Namibia are reducing the flood waters.

What worries Seikaneng Moepedi, the General Manager of the Okavango Kopano Mokoro Community Trust (OKMCT), the most, is not the increasing number of migrants from villages such as Boro and Xharaxau nor the persistent droughts. His main concern is that the migrants are becoming comfortable in their discomfort.

The new normal

“The presence of migrant polers and other new guides has attracted food, alcohol and entertainment providers. So, instead of saving their money and investing in new sources of livelihoods that are not as water-dependent as poling or as wildlife depredation prone like farming, migrants are wasting their income on things like alcohol and drugs,” explained Moepedi.

When these breadwinners left their children, wives, husbands, pregnant daughters, and parents following the 2018/2019 catastrophic drought which caused the world’s largest inland Delta to partially dry up, they settled at a place that would enable them to continue earning a living by offering tourists dugout canoe excursions. The OKMCT facilitated the services they offered to travellers.

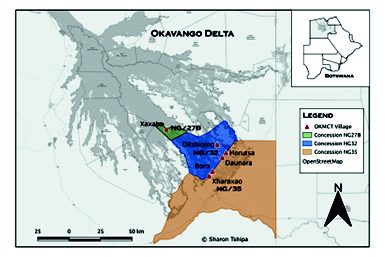

OKMCT is a community-based organisation (CBO) operating in a wildlife management and controlled hunting area popularly known as the NG32 Concession. The trust serves six Okavango Delta villages, namely, Boro, Daunara, Xharaxao, Xuoxao, Xaxaba and Ditshiping.

Of the six villages, Boro and Xharaxao, are now referred to as ‘ghost villages’, as they are characterised by an unusual emptiness, a hush abandonment following the drought that resulted in non-economic loss and damage impacts such as loss of cultural heritage, loss of ecosystems and biodiversity, loss of quality of life, as well as mental and physical health effects.

No sooner had the OKMCT aided the migrants’ relocation and added them to the list of local polers than the drought migrants realised that earning a living was not going to be as easy as they had hoped. This was because, in addition to local polers, Daunara Poling Station was compelled to host 300 climate migrants from three neighbouring villages.

What this meant was that a poler could go weeks or even months without hosting a single excursion, as customers were scarce. The arrival of the COVID-19 pandemic in this desperate scenario made the situation even worse. The health threat that tested, and undermined healthcare systems around the world drastically reduced -Botswana’s tourist arrivals, thus compounding the drought problem.

The outcome of the climate change-migration nexus therefore became increased competition, strained human relations, and hunger. Yet, returning home was not an option because traditional occupations and gender roles—including fishing, cattle rearing, and crop farming— had been affected. On the other hand, limited access to safe drinking water had led to diarrhoea and loss of lives within the greater region.

When copping measures fail

Migrating to Daunara was not the only coping measure undertaken. Setting wildfires to deter elephants, killing wildlife, migrating to cities for fear of drought induced human-wildlife conflicts, abandoning farming, reducing the number of livestock, digging wells and boreholes, and resorting to government safety-nets like Ipelegeng—a temporary employment program, were some of the coping measures practiced.

Yet, the vast majority of these have failed, exacerbating mounting mental health challenges experienced by the Okavango Delta communities.

To intervene, the OKMCT, led by Moepedi, took on additional responsibilities. The trust not only transported migrants to and from their homes whenever needed but ensured that they had access to regular medical check-ups and grocery shops. The trust also made sure that the education of the migrants’ children was not completely disrupted.

Despite the efforts made, the dire need for support that could emanate from innovative financing models and technical support mechanisms was expressed in 2023. Migrants hoped for investments in: i) water plants that could guarantee access to clean drinking water, ii) sound infrastructure development so that when rivers dry up people can utilise underground water, iii) boreholes, water harvesting and irrigation technologies, iv) the construction of additional watering holes along the delta, as these will ultimately reduce human and wildlife conflicts during drought periods, v) and the maintenance of buffalo fences or the installation of electric fences that can run between concessions.

With access to funds, communities also thought they could secure electric fences for their farms.

Two years later, none of these needs have been met.

People continue to suffer.

They are losing hope, and finding solace in what Seikaneng Moepedi calls addictive substances.

As a CBO, Moepedi’s Trust is expected to manage natural resources sustainably, providing local communities with economic benefits through tourism initiatives such as guiding, craft selling, and campsite management, while ensuring the conservation of the delicate ecosystem by actively involving them in wildlife monitoring and managing human-wildlife conflicts. All in all, the aim is to balance community livelihoods with environmental protection.

Faced with the polycrisis, the CBO could only do so much.

Urgent support needed

“Every year we have new guides who want to be licensed. We have no choice but to allow this even though it has increased the number of polers in Daunara by at least 50 new polers,” said Moepedi. “Our need for urgent support has become more pressing than ever given the competition for customers,” he further explained.

In 2023, Moepedi made a call for help, citing the need for various stakeholders to invest in the diversification of sources of income among Okavango Delta communities. This meant upskilling and equipping citizens with new ways of making a living. He also stressed the need to invest in the provision of technical assistance and training programmes for community-based tourism operators, as this would build their capacity to adapt to climate change impacts and implement sustainable practices.

What he thought would help migrants become even more resilient was access to small grants that can empower communities to implement their climate adaptation solutions, fostering local ownership and innovation.

Despite his appeal, and the hope-smothering crisis his communities are still facing, Moepedi said they have not received any assistance. Nonetheless, he is grateful that the COVID-19 pandemic is no longer an additional deadening factor.

“Between April and October, we tend to have an influx of tourists, which gives all our polers a chance to provide an excursion. Though things are better now, it is not enough because January and February constitute our low season,” he said.

Notwithstanding that, migrants no longer have to wait for months to earn a living. The fact remains that they are unable to return home as their own rivers are still dry.

“What we need to do now is to encourage mindset and behavioural change. To restore their hope, they need lessons in climate-smart agriculture, among other possible projects, and they need to be connected with stakeholders who can help them use their money wisely,” said Moepedi.

A two-day trip to the delta, he revealed can earn a poler over BWP1000 (USD72). If saved and utilised wisely, he believes the money can provide a sustainable and long-term source of livelihood.

“Should this happen, I believe that migrants will be able to return home,” he enthused.

What gives him confidence are the fruitful efforts of the OKMCT.

“We have a group of women that have since gone into vegetable farming. We are also helping young people who failed high school to retake the exams, while enrolling other youths into training schools—they often opt for tourism industry courses such as housekeeping, waitressing, tourist guide and being a chef,” he said. If made accessible, the Loss and Damage Fund could be used to enable migrants to return home, he added.

The Botswana government’s social protection programmes assist with seeds for farmers, and compensation following wildlife depredation, but Moepedi said government interventions are lacking as they do not necessarily respond to the climate crisis—if they do, he said, they are not communicated adequately.

“Projects like fish and poultry farming, for eggs, would be useful, especially if undertaken along the buffalo fence,” he said.

When migrating or cohabiting are not ideal choices, but options are limited

While this article’s focus is Daunara, it is important to note that Morutsa and Ditshiping Poling Stations have also received their fair share of migrants. This means that a large number of people are in serious need of help. Since the grass always looks greener on the other side, polers have occasionally moved from one poling station to another, only to realise that no other migrants have it better.

Failure to counter the impacts of loss and damage, Moepedi therefore says will only increase the number of migrants living in make-shift shelters, as is currently the case.

Migrants who have returned home so far are other Okavango Delta residents like Tiny Ratshipa of Tsanokona village, whose main reason for migrating was the fear of elephants.

“My teenage daughter and I took refuge with friends in Maun, and we dependent on organisations like Love Botswana for livelihood needs like groceries. We returned home after noticing that our host had developed hosting fatigue, she needed her space,” she said. “I am a woman living with a disability following a stroke, getting help from the government has been a challenge,” Ratshipa added.

When the 2018/2019 drought hit, she had invested all of her late husband’s pension fund benefits into an agri-business with the hope that it would help take care of her kids, but elephants came and destroyed it all, including the solar lights she had installed.

Feeling that their lives were under threat, they abandoned their farm home. Though nothing has changed, they had no choice but to return.

Now, they keep a watchful eye every day, they stay alert.

“There is nothing we can do but learn to cohabit with the elephants and stay safe. Because of the recent rains, elephants have moved back into the delta, but we know they will come back once their water sources dry up. If only the fence could be fixed, that would control their movements,” she said.

Living on the edge like this cannot be good for anyone’s mental health, hence the need for rapid economic and non-economic loss and damage interventions that can also ensure that the gains of the Sustainable Development Goals are not completely undone.

This article was written by the author revisiting a case study she prepared in 2023, titled ‘Fighting a losing battle? A case study tracking ecosystem loss in nature-dependent Okavango Delta communities of Botswana’. The case study was included in the compilation ‘Living in the shadow of loss and damage: uncovering non-economic impacts’ published by the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED) and can be accessed at https://www.iied.org/21891iied.

Author

Sharon Tshipa is the Chairperson and Co-Founder of Botswana Society for Human Development. She is also an award-winning freelance multimedia journalist based in Gaborone, Botswana. Read more about Sharon @ https://lossanddamageobservatory.org/profile/Sharon/NTc=