Photo credit: author’s own

Tulsi Devi Bhatt, draped in an embellished purple sari and a full sleeve red kurti (top), navigates her way through the wheat fields in Hinta village in the western Indian state of Rajasthan’s Udaipur district. She is on her weekly mission to measure water level in the dug wells – the quantity of water is critical for the food security and livelihood of her community.

Hinta is part of the two multi-village, hard rock aquifer watersheds – the 6400-hectare Dharta watershed in Rajasthan and 5000-hectare Meghraj watershed in Gujarat, where MARVI – Managing Aquifer Recharge and Sustaining Groundwater Use through Village-level Intervention – project has been instrumental in enhancing groundwater recharge and availability.

Spearheaded by the Western Sydney University in Australia, working in collaboration with seven other partners in India and elsewhere, the MARVI project is aimed at empowering farmers like Tulsi with the knowledge and tools necessary for sustainable and equitable groundwater management in their villages.

Tulsi, who quit school after 8th standard, is amongst the many Bhujal Jaankars (BJs), a Hindi word meaning ‘groundwater informed’ local volunteers, being trained by MARVI researchers irrespective of their level of formal education. The BJs monitor and measure the quality and quantity of groundwater levels in the dug wells and check dams, take readings from the rain gauge, and also receive training in recharging aquifers.

About 2-meter-deep groundwater recharge pits have been built near the dug wells to capture surface water run-off for recharging. Tulsi lowers a float to touch the water surface inside the dug well and uses a measuring tape to take the reading. She meticulously records the measurements and readings in her diary and also uploads the hydro-geological data collected in her smartphone and SMS-based App, MyWell. This data is then shared with MARVI researchers to check for accuracy and provide the necessary scientific input. The BJs then relay the information to the village farmers and help them make an informed decision on what crops to plant based on the availability of water.

“When the monsoon rainfall is good, we plant water-intensive crops such as wheat and corn. During average rainfall, mustard, chickpeas, Isabgol (Plantago ovata) do well”, says Chanda Choubisa, adjusting her embroidered smartphone pouch tucked at the waist. She has 0.3 hectare (1.5 bigha) farmland and uses a tubewell for irrigation.

“Groundwater is our lifeblood. We need to conserve and manage it wisely because our income and sustenance depends on it”, she adds as the blanket of morning mist gradually gives way to winter sunshine.

Along the way, a woman is herding her goats under a Khajur (Phoenix sylvestris) tree, another woman in a red-green kurti and ghagra (long skirt) is carrying a load of firewood on her head; nearby a group of women are filling their pots from a tubewell next to a homestead painted with traditional motifs of plants and animals.

Women in rural communities traditionally bear the burden of water-related chores. Water stress has been intensifying in rural communities with climate change driven extreme heat and erratic monsoons. The United Nations World Water Development Report 2024 states girls and women are the first victims of a lack of water.

“Central to MARVI’s success is its recognition of gender dynamics in groundwater management through targeted initiatives, such as mentoring young girls in schools to become water-literate BJs and promoting women’s leadership in village groundwater cooperatives (VGCs)”, says Professor Basant Maheshwari, who leads the MARVI project at the Western Sydney University.

“MARVI embodies a paradigm shift in groundwater management, empowering and engaging local communities to become stewards of their water resources and linking them with researchers, NGOs and government agencies”, adds Prof. Maheshwari, who grew up in Hinta and has had first-hand experience of the devastating impact water scarcity and drought have on village communities, their farms and cattle.

This farmer-centred project approach has resulted in recharging of groundwater aquifers, reducing risk of crop failure, improving yields and as a consequence increasing smallholder farmers’ incomes, and opening more local employment opportunities for the villagers.

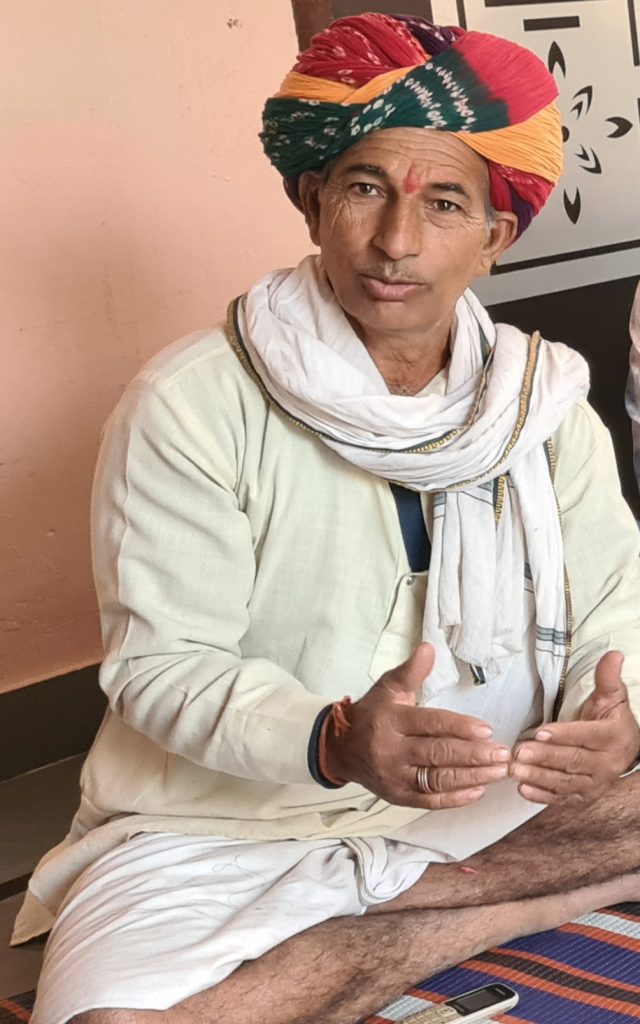

Many men, who had migrated to nearby towns and cities in search of work as labourers and cooks, are now returning to cultivate on fallow fields as earnings from agriculture is paying rich dividends. Ratan Lal, a BJ now, used to work in an ice-making factory in Ahmedabad.

He says, “Our wells were dry and soil was too parched for agriculture. Since the project started in 2012, we have seen the water table in our wells rise from 80 feet deep to now 20 feet deep. I have been able to nearly double my income with better crop production, using much less water. Most importantly, there is hope for a future here in the village itself”.

Agrees Bhanwar Lal Rao, another BJ. “Community involvement in the project is changing attitudes. Villagers are aware that water is a limited resource and they need to use it wisely. As we haven’t had good rains this year, I planted less water-intensive chia (Salvia hispanica) on one hectare. It reaped 1500 kg of chia seeds with a market value of INR 450,000,” he tells this correspondent with a beaming smile.

Rameshwar Lal Soni and his wife Manju Soni enrolled as BJ early in the project. He says, “We are training villagers to use mulching to prevent evaporation, which is being magnified by extreme heat; and drip irrigation which is helping conserve up to 80 percent water use.”

BJs like Hariram Gadri, who has been farming for nearly four decades in Dharta village, are now mentoring other villagers to become water-literate BJs. He says, “For us farmers, water is more important than blood. If there is water, there is life”.

Hariram is advocating for BJs to be formally connected with gram panchayats (village councils) so their skills can be utilised in groundwater and other natural resources management schemes.

“The MARVI approach is being applied in the Indian Government’s Atal Bhujal Yojana, which included village-level monitoring and management of groundwater for developing village water security plans”, says Prof. Maheshwari.

The farming community in the two watersheds are also piloting the concept of sharing groundwater through forming village groundwater cooperatives (VGC). There are 3 VGCs each in Rajasthan and Gujarat.

“We have realised that deepening individual wells or installing deeper tubewells will not solve our groundwater problem”, says Devi Lal, who is sharing water at no cost from his tubewell with other farmers in the VGC through an irrigation water pipeline connecting 22 hectares of farmland.

This is helping villagers share groundwater in a sustainable manner and also minimise power use for water-pumping motors – demonstrating the transformative potential of grassroots empowerment and local community-driven initiatives in addressing water scarcity.

The MARVI approach is expanding beyond India. A recent scoping study conducted in Lao PDR, Indonesia, and Timor-Leste has revealed that MARVI could be a valuable tool for addressing the unique groundwater challenges faced by these countries.

“MARVI could help provide training and support to communities for data collection and analysis; and more proactive groundwater monitoring and management by building local decision-making capacity and promoting sustainable water use practices in the Asia Pacific region”, says Prof. Maheshwari, underscoring the critical need for incorporating gender equality and social inclusion throughout MARVI implementation.

Some facts

- MARVI led by Western Sydney University works in collaboration with seven other institutes – Maharana Pratap University of Agriculture and Technology and Vidya Bhawan Krishi Vigyan Kendra in Udaipur, Development Support Centre in Ahmedabad, Arid Communities and Technologies in Bhuj, CSIRO Land and Water in Australia, International Water Management Institute’s India office in Anand, and Mekong Region’s Futures Institute.

- The BJs have been monitoring the water table in 250 dugwells in Dharta watershed and 110 dugwells in the Meghraj watershed.

- The BJs go through theoretical and practical 45-day training program in their local language on mapping, land and water resource analysis, geo-hydrology, water balance analysis and groundwater management strategies.

- There are a total 365 BJs across 324 villages in Gujarat, Rajasthan, Chattisgarh, Madhya Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra states of India, where the MARVI approach for sustainable groundwater management is being used.

- The project has enlisted support from UNDP and industry partners, such as, Adani Foundation, Ambuja Cement Foundation, and Coastal Gujarat Power Limited, a subsidiary of Tata Power, amongst others.

- The project was initially funded by the Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) and Australian Water Partnership (AWP). The AWP funding is continuing.

- The recent scoping study in Lao PDR, Indonesia, and Timor-Leste led by Western Sydney University is funded by Australia’s Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade through the Australian Water Partnership.

- The Central Ground Water Board (CGWB), a key governmental organization responsible for assessing and managing groundwater resources in India, published the ‘Dynamic Ground Water Resources Assessment of India – 2022‘ report last October. The major source of groundwater recharge is monsoon rainfall, which contributes about 55% of the total annual ground water recharge. Rainfall during the monsoon season contributes more than 70% of the annual ground water recharge in states like Gujarat and Rajasthan. Groundwater level data for 2021 and 2022 reveals that the general depth to water level in the country ranges from 5 to 10 mbgl (metres below ground level). The stage of groundwater extraction is very high in states like Rajasthan where it is more than 100 percent, with agriculture being the predominant consumer of groundwater resources, accounting for about 87% of the total annual groundwater extraction.

- 5 Bigha = 1 hectare. The conversion ratio varies from state to state.

Author Biography: Neena Bhandari is a Sydney-based journalist, who has previously lived and worked in India and the United Kingdom. She writes on a wide range of subjects, including environment and development, and health and science, from the Asia-Pacific region. She had visited Hinta and Dharta villages in December 2023.

Good blogs thanks